Saul Levine: FM Radio Pioneer | Telos Alliance

By The Telos Alliance Team on Jul 31, 2014 11:00:00 AM

Saul Levine: FM Radio Pioneer

Saul Levine: FM Radio Pioneer

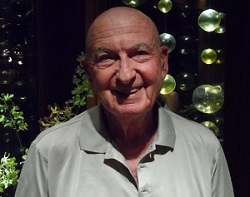

Saul Levine, one the pioneers of FM radio in Los Angeles, has been operating KKGO 105.1 since February 1959. Through his company, Mount Wilson Broadcasting, KKGO is the oldest, independent FM station in Los Angeles and one of the very few independent FMs remaining in any major market.

The station originally signed on as KBCA, became KKGO, then KMZT, then returned to the KKGO call letters in 2007. The station began as a classical music outlet, then had a long-running jazz format, returned to classical, and finally adopted a successful country music format.

Recently, Omnia Brand and Marketing Manager Denny Sanders spoke with Saul Levine at his Los Angeles headquarters.

Saul, you grew up on a farm in northern Michigan and then studied law and ran a wire d background music service out of your apartment. Was that in Los Angeles?

d background music service out of your apartment. Was that in Los Angeles?

Yes.

What brought you to L.A. from northern Michigan?

Well, the way it started out, at the age of 18, I went to the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. But my ultimate goal was not to return to this small place. It was just a one stoplight place lacking in any culture, although the environment was nice, the lakes and skating out in the winter and the snow, but very, very cold. It would start getting cold, snowing in about the end of October, November, and then not ease up until literally April or May. Then the summers were really hot and intense.

I wanted to move to Los Angeles where the activity was, where things were happening. So I moved out to California but actually ended up transferring to Berkley. I finished up my BA at Berkley and got a job with the County of Los Angeles as a social worker. I thought that might be a good field for me, working with people. Then I went to USC and got a graduate degree, a two-year graduate degree. I decided that my heart really did lie in broadcasting and, as an interim thing, in law. So I went to law school at UCLA, got a J.D., came out and started to practice law. Then, I was fortunate to be able to secure 105.1 in Los Angeles.

This was in 1959. You were one of the only people back in those days who believed in FM radio when others were turning their licenses back to the FCC, even in New York and Los Angeles. There were almost no portables back then, and FM car radios were an expensive add-on. What made you persevere where others gave up?

It was simple. I believed in it. I just believed that FM offered a whole new form of broadcasting, high fidelity. Surprisingly, at that time we did not have high fidelity recordings. The dilemma was, we were broadcasting music literally in low fi, probably 8000 to 9000 cycles max, if that much.

Was that because of your STL limitations to the transmitter?

No, there just weren't the recordings. The recordings were still 78 RPM and just getting into LPs. So there was not high fidelity. There was not stereo. Stereo was not authorized by the FCC until the early 60s. Then, it took years to be adopted. We didn't adopt stereo on our FM until 1968. There was this lag, plus the lack of receivers.

So, tell us about how you put 105.1 on the air up on Mount Wilson in 1959. It's truly fascinating.

What happened was, I was able to get the Construction Permit. I did all the work myself. I didn't have any funds and I was able to do the engineering, perform the legal, and file it. There was no filing fee. The only fee was getting the prints. That cost me about $25. I found that I had a Construction Permit, but with no money to put it on the air.

I had been running this background music service out of my bedroom while I went to law school. I was a one-man company. I would go out and sell the service to locations.

Muzak at that time, by the way, was operating over land lines too. I was able to get about 25, 30 accounts, program them from my apartment with a Seeburg-100 jukebox. What that consisted of, it had 100 slots and would automatically go down the row and play them all. They were 78 RPMs. Around the same time, I had developed a friendship with a gentleman from Nebraska, Evan Wilson, because he was selling electronic components, which I needed.

So, over a period of three, four years he trusted me. So, I came to him and said, "I'd like to borrow $10,000 from you." He said, "Fine." So, I got the initial money to put the station on the air. I was fortunate. Raytheon actually had operated an FM station in Waltham, Massachusetts and then took it off the air because of a lack of belief in FM, too. I was able to buy the transmitter for $1500, plus a Hewlett Packard 335B modulation frequency monitor.

Now, I had the essence of getting on the air right there. I needed an antenna, though, for that transmitter. So I had a gentleman I had met who was really a tower rigger and he made this antenna for me for about $300 in his garage. It was a very interesting antenna. It was a solid piece of pipe. The radiating elements were pieces of pipe, which he had bent into a circle to imitate a Collins ring type. Then, he welded them to the supporting pipe at three-quarters wavelength. But, then, in between, he ran RG- 11, which was a full wavelength. That was a very interesting idea. We got on the air with that.

It wasn't more than a matter of a few days when, between icing - there were no de-icers on it - and lightning strikes, it burned up the antenna. So, I then resorted to another gentleman who made antennas in his garage. He actually made a pretty decent Collins-type ring for me for also a few hundred dollars, and we got back on the air.

Tell me what suspended this antenna on top of Mount Wilson.

We had a flag pole. We had a 100-foot flag pole. This is an interesting story. I guess I'm a better salesperson than I realize. I went to a flag pole company and sold them on the idea of getting barter on my station, which was not yet on the air. They delivered and installed a derrick 100-foot flag pole. Then, we mounted the six-bay antenna on it, and we were in business.

And from this flag pole on Mount Wilson, KBCA went on the air in early 1959 broadcasting classical music.

Correct. The construction actually took place in the end of 1958. I put a little shack up for $5000. It was really more than a little shack. It was an 18 by 24-foot building on a concrete slab. We still have that building today. It's held up, except for a new roof or two. It's still very useable.

But, I ran into another calamity. Earlier, in '58, I had managed to convince a hotel to let me build my studios for barter, mentioning the hotel on the air. At the same time, there was a huge forest fire on Mount Wilson and the Forest Service wouldn't let me build the transmitter.

Since I couldn't perform, the guy that let me use the hotel as his studio became very impatient with me, decided that I really was deceiving him, and that I never planned to put a station on the air. So, I was kicked out of the hotel, had to remove all of my equipment, and lost all of the money I had spent to construct it. That's why I had to go up on Mount Wilson and, when we did operate, operate from there until I could relocate.

So, the original studio was at the transmitter site on Mount Wilson.

Well, not by choice but, by necessity. Yes. I was very fortunate. I had this engineer, who was also an announcer and loved classical music and knew the pronunciations. He was a Seventh Day Adventist, and they lived off of vegetables, berries and herbs. So, he went up to the mountain with a sleeping bag - no food, no running water - and lived off of berries and so on.

He put the station on the air that momentous night of February 18th, 1959 which I'll get to in a moment. So, John George... he actually had two first names…. would climb the tower, too. Nothing scared him. Sometimes we had to have somebody climb and he'd climb the 100- foot pole and fix things on this antenna, which periodically would go out.

How many hours a day were you on the air at that time?

Well, we went on for 18. He wanted to operate 24. I said, "John, you humanly can't do it." He said, "I will. I'm going to set an alarm clock and at midnight, I'll go to sleep, put a recording on for 20, 30 minutes, and then the alarm clock would wake me up." So, he did that for one week and, of course, he couldn't maintain that. So, we were operating from 6 a.m. until 12 midnight.

You signed on as a classical station, but then switched to a jazz format somewhere in the 1960's. Can you tell me when that was?

You signed on as a classical station, but then switched to a jazz format somewhere in the 1960's. Can you tell me when that was?

Yes, it was early in 1960, probably around January, February, as I recall. What happened was, with classical, we had incredibly fine programming, but the classical station in L.A. that was on AM, KFAC, also had FM and gave the FM away. So, advertisers didn't care if we had a better format and execution of it. They just said, "We get FM free."

So, I was really in serious trouble. I'd spent all my money and working hard in law to sustain the FM station, when a guy named Daddy-O shows up. He said, "May I buy the time between midnight and 6 a.m. and I'll pay you $500 a week?” That was money from heaven. I said, "sure." Then, once this jazz got on the air, two guys, Tommy Bee and a fellow named Jack came by and they said, "We'll pay you $300 a week if we can have the afternoon time”.

Tommy was a known figure in jazz and was well liked. His theme song was Miles Davis' "Miles Ahead." That helped take off. Then, a Chinese broadcaster from San Francisco named Lee came to me and said, "I'd buy 10 p.m. to midnight for a Chinese program and pay you $200 a week," which would pay my rent. So, before I knew it, I was broadcasting 24 hours a day. For the first time, I actually was paying my bills and coming out ahead.

Now, who was Daddy-O? Who was this guy that really started the jazz programming on the station?

I don't know what his background was. He just showed up. He was African American. New jazz. I was a little put off going from Beethoven and Mozart to a guy named Daddy-O! The reality was that I wanted to save the station, for obvious reasons. By the way, the channel had gone dark. A major AM station in L.A. had put it on the air, lost faith in FM and took it off the air. So, I had a vacant channel, which today, as you well know, is worth a lot of money.

It sure is. Being in Southern California with the jazz station all those years, I'll bet you had some very famous listeners and supporters.

Oh, I did. I did. Very famous. As a matter of fact, just going through some letters I had saved, there was a letter from Dinah Shore, the actress, how much she loved listening to our station. I had all celebrities in, as well as regular people. We had a huge audience, but it was also very hard to market. Most of the business was barter. Sometimes I would take the barter and resell it to someone else for cash. So, I did everything I could to stay in business back then.

That leads me to my next question. What was it like to sell advertising on a FM standalone back then? Did you have to hand out FM radios? I mean, it was still not yet a mainstream service.

That leads me to my next question. What was it like to sell advertising on a FM standalone back then? Did you have to hand out FM radios? I mean, it was still not yet a mainstream service.

Correct. We had about a 30% penetration of the market at that time with FM. In my car I had to buy a Motorola attachment. It was a tuner, and it fit under the dash. By the way, it worked very well.

But, we had another problem, because we were broadcasting in horizontal polarization only. We had a lot of picket fencing when you were driving. It was really a handicap. So, when elliptical and then circular polarization came out, I jumped on it. That's how the problem of picket effects was addressed. Talking about my interest in cutting-edge technology, I put on the air the first elliptical polarized antenna, at least on Mount Wilson, if not on the West Coast. Then, when circular came out, I jumped on that.

And you were the first to put radomes up there too, right?

We were the first, yes, which was soon adopted by others when they saw that we could keep operating when the antennas were beginning to ice up. And they did. We also were constantly evolving our technology on antennas. We started out, again, with this pipe thing, which burned up in no time. Then, I switched to a home-made six-bay Collins ring type, which worked pretty well. Then, I bought a Jampro. They came on the scene and we went to a four-bay. Again, further evolving into trying to get rid of those nulls from the antenna, we went to a two-bay, which we now operate with today, and it's very successful.

I find this remarkable that you blazed these trails in an era when the big groups, like CBS and ABC and others in Los Angeles had all the money in the world but none of the vision for FM that you had.

You see, FM to them was a holding action. Actually, RCA and Mr. Sarnoff tried to kill it. There's history on that.

Yes, with Sarnoff reportedly using his influence to change the band in 1945 rendering every FM radio at the time useless.

Yeah. That's why in the 30's they sued Armstrong, the innovator of FM broadcasting. They drove him to suicide, unfortunately.

Saul, you always seem to pick formats, which are either for a more sophisticated audience, like jazz or classical, or for an underserved audience—at least in LA—like country. Is this an extension of your philosophy, or a strict business decision, or both?

Saul, you always seem to pick formats, which are either for a more sophisticated audience, like jazz or classical, or for an underserved audience—at least in LA—like country. Is this an extension of your philosophy, or a strict business decision, or both?

It's not a business decision. It's an extension of my personality and cultural leanings. On the AM, I have presented adult standards when no one else wanted to do it. So, we've taken these niche formats. Then, in August of 2006, KZLA – owned by Emmis – dropped their country format and came on with rock programming.

Just fortuitously, my son, who works in business with me, was having dinner at home. Country had been off the air in L.A. for about three to four months. People were clamoring for it. After dinner, we were drinking tea and Michael turned to me and said, "Dad, there's this big niche opening for country and, you know, it's still a struggle to sell classical." He said, "Why don't we go country?" I looked at him and this hurt, because I loved the classical programming that we had returned to in 1990. I said, "Okay, let's do it."

We knew that Clear Channel was looking to do it too. So, we put together the format, kept it quiet, and, in fact, Clear Channel had called me because they had rumblings we were going to go with country. They said, "Don't do it. We're going to do it." I beat them to the gun. We were on the air seven days later with country and it's been very successful. As far as my history of niche formats, this is a super niche format because we have over one million cume listeners.

Yes, country isn't exactly a niche format like jazz or classical. But, in L.A., you filled a void.

Yes, we did. We have to work very hard, even with this format, which is number one in many markets across the country. Because the composition, 45 to 50% is Hispanic and the Hispanic listening to country is very small. The African American population in the market is about 7%. Asian is about 15%. So, actually, we are appealing to mainly a Caucasian, which is now down to 30-35% of the market. The big guys said it can't be done. You can't make it. Well, we're now in our eighth year and we're making it.

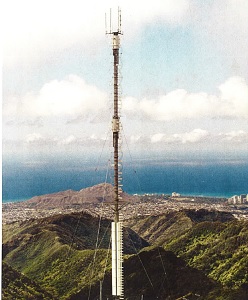

I want to switch gears for a couple of minutes. In the 1970s, you were responsible for the first high- elevation transmitter site in Honolulu. No roads, no power, no nothing. How did you pull that off?

That is one of my, I feel, personally, one of my crowning achievements, on a small scale. But, I'll tell you what happened. I decided to get involved in radio in Honolulu because FM had not been developed there.

There were only six stations on the air on FM and they were all just simulcasting their AMs, as what happened in L.A. I loved the climate there and I was married then and I had little children, who could grow up on the beach there. So, I was going to build the first FM there, but everybody else was on the rooftops in Waikiki.

Now, Honolulu, Oahu is split in half with a mountain range, which meant the other half, the windward side, could not get FM reception. So, I decided I was going to go up on top and serve the entire island. It was quite a challenge.

I found this spot about 2500 feet above sea level and it was on state property. I filed an application with the state to build my transmitter there. I went into hearings before the state with tremendous opposition from environmentalists... little old ladies in tennis shoes showed up at the hearings and opposed it. Finally, the state gave me the authorization.

Then, the next step was, I had to build it. There was no electric power. There was no road or access. It's on a former volcano, which has steep slopes, maybe 45 degrees. I was then faced with this dilemma. So, I prefabbed the building in Los Angeles, a 12 by 24-foot steel building in sections, and got a helicopter to airlift it up there. The closest I could get to a contractor who would assemble this on a base was a quarter of a million dollars, which I didn't have.

So, I decided to sub it myself. I had the building there in parts up on top of this ridge. I didn't have a contractor, so I had found a guy who was a sub, a cement installer. I got him to go up there and we had to put the footings in on the side of the slope. The trail up there was on about three, four feet, so the building had to rest on the trail and the other half on the slope. That had to be supported by pipes that were, perhaps, 20 feet long. So, I got them to do it and it was approved, but I didn't have electric power.

Hawaiian Electric delegated the work to me, which meant, I had to actually put the electric poles in and span a valley of about half a mile between peak to peak with this electric cable. I planned to use a local helicopter that could carry 750 pounds, for 40-foot poles, but then The State of Hawaii revised the rules. I now had to use 60-foot poles, and they weighed between 1500 and 2000 pounds and the only helicopter I could rent on Oahu could not carry the weight required under the new rules. Here I had a building that was now built, I had a tower with an antenna on it, and I had no electricity. And there was no way to get any up there because there were no helicopters except the military, which would not help.

My attitude was, don’t give up. I called every helicopter company in Los Angeles. I found one that had some down time and made a deal with them. For $20,000 they would disassemble a helicopter, which could carry 2000 pounds, put it on a Matson steam ship liner, which would take five days to get over there. They would reassemble the wings and the propeller when we got there.

I would have the holes dug already. They would just pick those poles up from Hawaiian Electric, fly over my site, drop them in the holes, fly back to the airport, and put it back on the ship, which would take about a total of two weeks. So, I grabbed the deal, because otherwise, I was out of business and it worked like a charm. They came in, reassembled the helicopter, picked up these 60-foot poles, carried them over to my site, dropped them in, went back and got about half a dozen of them, and then went back to ship and went back to L.A. So, I was able to save that situation.

I’ll bet there are probably several stations up there on that site today.

Well, yes. The first one that wanted to go up there was Hawaii Public Radio and they went up there immediately with me. We went on the air officially in October '78. They went up there with me, but I had a lot of flak from the environmentalists trying to throw me off, kick me off the mountain. So, as a gesture of goodwill, I have donated that space to Hawaii Public Radio. I've never gotten a dime from them.

Well, yes. The first one that wanted to go up there was Hawaii Public Radio and they went up there immediately with me. We went on the air officially in October '78. They went up there with me, but I had a lot of flak from the environmentalists trying to throw me off, kick me off the mountain. So, as a gesture of goodwill, I have donated that space to Hawaii Public Radio. I've never gotten a dime from them.

We're up there now, and finally another group went up there, and there are two other transmitters up there. So there's a total now of my original station and two other commercial and Hawaiian Public Radio, plus a UHF TV station. But I also want to tell you about the call letters, which I take great pride in.

The station is officially licensed to Kailua, which is a suburb of Honolulu. So I took the call letters KLUA. I thought that would be really cool. Well, I started operating and some locals called me and said, "You don't know what that means in Hawaii. That means the toilet." I said, "I can't do that. I can't do that." I changed it immediately to KKAI, but I wasn't happy with that.

So, my wife and I were at a movie theater in Honolulu and there was a movie called "Romancing the Stone." Anyway, the plot was that they were flying a cargo plane against people who were trying to shoot them. They crash landed and a box, a crate, came out and on the crate it said, "crate." So, I turned to my wife and I said, "We turn that into "crater." She said, "I love it."

Immediately, when we got back to the hotel, I checked all the call letters in Broadcasting Magazine for KRTR. I called my attorney in the morning in D.C. and said, "I want KRTR." So, we became KRTR, and they're great call letters being used today.

There's another aspect to your life. You have wine vineyards in Napa Valley and New Zealand? Just can't get the farm out of your blood, can you?

That was it. In the late '60's, somebody introduced me to fine wine because, to be candid, until that time, my only experience with it was Manischewitz, which is pretty horrible. Here, I was introduced to some really good wine, and I said to myself, "I'm a farmer. I can do that."

So, immediately I did research on it. It took me a couple years. I found 50 acres in Monterey County and I planted it to vines. But, I didn't have any money to speak of even then, since I was still struggling. Around 1970, I was still struggling. The FM in L.A. was still operating at a deficit and I was working night and day in law. What I would do, I would practice law in the morning, go to court in the morning, and then in the afternoon I would go out on the street and sell advertising. And I was doing that for year after year after year.

But, anyway, I wanted to get into growing grapes. So, I found this land, which I was able to pick up with a mortgage and I could handle it. I planted the vines but I couldn't afford to put in irrigation. In those days, irrigation was piping that went from one vine to the other above ground. So, I got into business with field irrigation, which meant that I had a well there, and you just flood the field. There was enough of a slope that the water would run down and water the vines. I did that for a number of years until things got better in L.A. and I could afford to put in actual sprinklers.

Then, in the meantime, just to finish the story on this, I found a farmer who would turn that field flooding on, but he wasn't reliable. I had to call him every day and say “please turn the water on”.

So, anyway, I found a really great g uy named Richard Smith - this was about a year later - who was doing farm work for other people. Richard still works for me today and he takes care of it and does a very fine level. Anyway, we finally got that structure going. But my goal always was to have Cabernet from Napa Valley, which is one of the places in the world to produce fine Cabernet.

uy named Richard Smith - this was about a year later - who was doing farm work for other people. Richard still works for me today and he takes care of it and does a very fine level. Anyway, we finally got that structure going. But my goal always was to have Cabernet from Napa Valley, which is one of the places in the world to produce fine Cabernet.

Do you market these wines under a particular label?

Yeah. It's called "Cobblestone." I'll give you the reason. The land that I bought in Monterey County is full of cobblestones. The way I discovered that . . . The way I first got the vines to plant, you take cuttings, branches, during the dormant season, put them in a nursery, which was across in the central valley for a year until they grow into rootings. Then, you take them back and plant them in your vineyard.

I was talking to the guy who was running this service with my rootings over there, and asked him if he had any ideas what to call the vineyard. He said, "Tell me something unique about it." "There really isn't much unique," I said, "in this valley. It's all filled with cobblestones." He said, "You've got your name. There's your name."

Anyway, that's why I called it "Cobblestone." We make a really great Cabernet now from Napa. I found that the grapes that do the best in Monterey because of the cool climate is Chardonnay, so we plant entirely Chardonnay there.

In 2008, my wife and I were on a cruise from Auckland, New Zealand to Sydney, Australia. Just by chance, we stopped off in Wellington, had the day to spend there, took a drive up to a very small valley called Martinborough. I sampled the Pinot Noir there and I said, "This is it. This is going to be my Pinot." So, I bought a small vineyard there and we've been making world-class Pinot, winning awards.

So, I have these three different vineyards and this is an innovative concept that you only grow the variety in each vineyard that is especially adapted to that climate. I've set a standard now in the industry. To my knowledge there's no one else on planet Earth that has three different vineyards in three different parts of the world and each vineyard is just devoted to the best grape that will grow there.

Well, Saul Levine, one of the great pioneers of FM radio in Los Angeles, wine aficionado and successful entrepreneur, it's been a pleasure to spend some time with you.

Before you stop, I want to talk about processors.

This is a subject that's very dear to my heart, just like FM antennas. By the way, in the '60s, I would sit around with engineers... Now, I'm not an engineer by trade. We would debate FM antennas. Anyway, getting to processors, I started out in 1959 with a Collins peak limiter. That's all there were in those days. You just limited the peaks so they wouldn't go over 100, which meant, particularly with classical music, with the extremes from low passages to high ones, we had a modulated peak of about 80%.

passages to high ones, we had a modulated peak of about 80%.

Anyway, we graduated from the Collins to the AudioMax, the Volumemax, and then to Orban, and then Aphex. But then, a year ago, I discovered the Omnia.11, and there's been nothing else like it under the sun. It has made my country station competitive. We have 18,000 watts on Mount Wilson, 6000 feet high. I'm up against Clear Channel and CBS with 50-60,000 watts.

We just have as equally good signal as they do. We cover three counties in addition to L.A. We come in like a local in Riverside/San Bernardino. We come in like a local in Orange County and we come in like a local in Ventura County as well, and of course in our L.A. County. So, I'm very, very grateful to Omnia for having developed this processor. We've bought five of them.

Thank you, Saul, for the kind words. Continued success and thanks for spending time with us today.

Thank you very much.

Telos Alliance has led the audio industry’s innovation in Broadcast Audio, Digital Mixing & Mastering, Audio Processors & Compression, Broadcast Mixing Consoles, Audio Interfaces, AoIP & VoIP for over three decades. The Telos Alliance family of products include Telos® Systems, Omnia® Audio, Axia® Audio, Linear Acoustic®, 25-Seven® Systems, Minnetonka™ Audio and Jünger Audio. Covering all ranges of Audio Applications for Radio & Television from Telos Infinity IP Intercom Systems, Jünger Audio AIXpressor Audio Processor, Omnia 11 Radio Processors, Axia Networked Quasar Broadcast Mixing Consoles and Linear Acoustic AMS Audio Quality Loudness Monitoring and 25-Seven TVC-15 Watermark Analyzer & Monitor. Telos Alliance offers audio solutions for any and every Radio, Television, Live Events, Podcast & Live Streaming Studio With Telos Alliance “Broadcast Without Limits.”

Recent Posts

Subscribe

If you love broadcast audio, you'll love Telos Alliance's newsletter. Get it delivered to your inbox by subscribing below!