Magnetic Tape and the Emergence of High-Fidelity Recording | Telos Alliance

By The Telos Alliance Team on Oct 18, 2017 12:00:00 PM

Magnetic Tape and the Emergence of High-Fidelity Recording

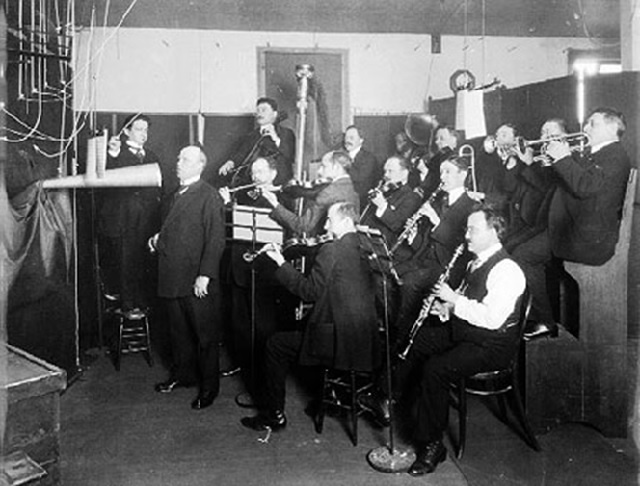

In the earliest days of sound recording (late 1880s to 1926), all recordings were made acoustically. That is to say, a recording machine with a large horn with a needle on the other end was set before an orchestra and the vibrations from the needle would “draw” a pattern on a spinning wax cylinder (or later flat disc). If a vocalist was called upon to sing, they would stand before the horn and sing right into it.

|

| Acoustic recording session circa 1920 |

Western Electric engineers H. C. Harrison and Joseph P. Maxfield worked on what they called “electrical recording” for several years before announcing it to the public in 1924. By 1926, the “electrical recording” technique completely replaced the old acoustic method, where a microphone or group of microphones would be fed through a basic mixing board, which would allow for the proper mixing of various instruments in the recording process. If there was a vocalist, they too would be properly mixed into the presentation. Through the use of a microphone and an electronic amplifier, an electromagnetic cutting stylus was used to cut the recordings. For the first time, it was possible to hear softer sounds like the letter “s” in song lyrics as well as more nuanced reproduction of certain string instruments. It also ushered in the era of the crooner; singers who would sing softly and intimately close to the microphone, the most famous of which was Bing Crosby (more on him later). Although still not high fidelity, electrical recording also allowed for a truer reproduction of the lower instrument registers as in this comparison of clips of one of my favorite pieces, Gershwin’s "Rhapsody In Blue."

By the way, I have a special treat at the conclusion of this blog.

However, the master recording was still made in the studio by cutting into a wax disc. Not only were there restrictions in fidelity, but the recording had to be made in one take as there was no practical way of editing portions of different takes together.

Magnetic recording was in limited use at the time, by recording on wire or steel ribbon, but the fidelity was substandard and these techniques were mostly dedicated to recording speech. Plus, recording on wire was a nightmare. If the wire came unwound it was extremely difficult to put it back. If it broke, it had to be welded back together. Steel ribbon wasn’t much better, plus the sharp edges of the steel tape running at high speed could give you a nasty slice.

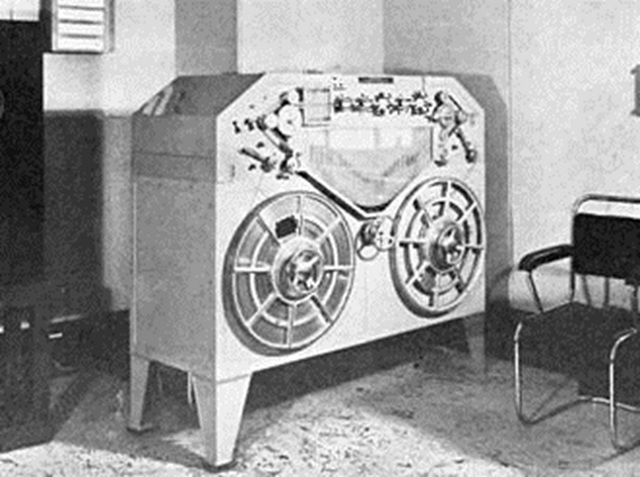

|

|

Early steel tape recorder at BBC. Still not good enough for music, only speech. 20 minutes total recording time on giant reels at 5 feet per second. Also made a great meat slicer! |

Although the idea to coat a tape of soft material with a powdered magnetic substance was proposed in Germany and the United States in the 1920s, nobody had managed to create a practical example. In 1928, German engineer Fritz Pfleumer got close when he coated paper tape with iron oxide to create a crude “recording tape” and made a record/playback machine. While this machine had all the fundamental elements of a tape recorder, it lacked in fidelity and could not produce a satisfactory quality of sound. The coated magnetic paper tape did not have an even surface and the coating was not very well attached; during playback the magnetic particles would scatter on coming into contact with the head. The machine never advanced much past the experimental stage.

However, in 1932, the president of Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG) in Germany showed some interest, buying the patent rights from Pfleumer. AEG immediately set up a research laboratory on magnetic recording and set about improving the machine and the tape. AEG realized that the paper tape was impractical, so they called upon the IG Farben organization (later called BASF), who worked on developing a more practical type of recording tape, while AEG worked on a machine.

By 1935, AEG was ready with an improved machine and BASF had the tape. The first machine went on display at the Berlin Radio Show in 1935 as the K1 Magnetophon, the world’s first practical tape recorder.

|

| Magnetophon as introduced at the 1935 Berlin Radio Show |

AEG developed several other models after the K1 Magnetophon, including a portable model. These began to be used for monitoring radio broadcasts and for military and police use. However, although relatively easy to use with the advantage of immediate playback, the Magnetophon’s fidelity was still substandard when it came to recording music. The breakthrough came in 1942 with the adoption of AC bias, the addition of an inaudible high frequency (generally from 40 to 150 kHz) to the audio signal. Adding AC bias increased fidelity and noise reduction to the point where music could not only be recorded on tape, but the quality now surpassed that of the best disc recording techniques of the era.

The Germans began broadcasting high-quality, pre-taped material all across Europe. The Allied Forces, realizing that such high-quality broadcasts could not possibly all be live originations, realized that the Germans had developed some kind of advanced recording capability.

Among surviving recordings is a late 1944, high quality, experimental STEREO tape recording of the Berlin Symphony Orchestra performing as the allied forces were bombing the city. Listen closely during the quiet passages between 5:43 and 5:57 and you can actually hear the bombing in progress.

Just before the Second World War ended, a member of the US Signal Corps, Jack Mullin, was posted to Paris where his unit was assigned to find out everything they could about German radio, their emerging television system and recording devices. On his way back home to San Francisco, Mullin visited a German radio station which was already in American hands. Here he was given two Magnetophon recorders and 50 reels of BASF tape. Mullin had them shipped home and over the next two years he worked on the machines constantly, modifying them and improving their performance. His main hope was to interest the Hollywood movie studios in using magnetic tape for movie sound recording.

|

| Magnetophon tape recorder discovered at a German-controlled radio station in 1945. |

In 1947, Mullin gave two public demonstrations of his machines in Los Angeles. In a dramatic presentation, he had live musicians perform from behind a curtain followed by a playback of the performance, also from behind the curtain. The demonstration was a smash hit since reportedly no one could tell the difference between the live and recorded versions.

Bing Crosby heard about the event and received a personal demonstration. Ever the savvy businessman, Crosby saw the huge commercial potential in high quality tape recording, but also had a personal interest: In the days of network radio, all programming was done live for transmission quality, and each program was actually performed twice - once for the East coast and again three hours later for the West coast. Crosby hated doing two shows, plus he also saw the potential of pre-recording and editing the show, re-taking songs that he felt he could have sung better, and recording the show “long”, so any ad-libbing could be edited out.

Crosby invested $50,000 (about a half million in today’s money) in a small, local electronics firm, Ampex, and the tiny operation soon became the world leader in the development of tape recording. Ampex revolutionized the radio and recording industry with its famous Model 200 tape deck, developed directly from Mullin's modified Magnetophons. Crosby gave one of the first production models to musician Les Paul, which led directly to Paul's invention of multitrack recording.

|

| Vintage Ampex ad with Bing Crosby |

NBC, Crosby’s network, refused to go along with the idea of pre-recording regardless of how good it sounded, so Crosby jumped ship to the newly formed ABC radio network, who were happy to let him pre-tape in exchange for having such a big star in their stable.

The ratings were as strong as ever and few realized that the program was not live, except for the sharpies who understood what the phrase “transcribed from New York, it’s the Bing Crosby Show” meant.

Vintage Bing

- Disc Recording of a live Crosby broadcast, not suitable fidelity for playback on air (1947).

- Just one year later, the Crosby program is pre-taped (1948).

Soon, just about every major program on network radio was pre-taped.

Magnetic tape also revolutionized the recording industry, as by 1949, most studios had switched to using tape as opposed to direct-to-wax recording. Like with the radio shows, this allowed for portions of several takes to be seamlessly spliced together for a perfect performance, and eventually for the use of overdubbing and multi-track recording.

As an added note, the first tape recorder designed exclusively for home use, the Brush BK 401 Soundmirror, was developed and manufactured not far from The Telos Alliance headquarters by Brush Industries, then located at E. 40th St. and Perkins Avenue here in Cleveland. Brush was quite a company in its day, offering a wide range of products, including high-fidelity microphones and speakers, as well as transmission equipment which was used by Admiral Richard E. Byrd on his second Antarctic expedition in 1934.

|

| Brush BK-401 home tape machine (1947) |

And now the treat.

I told you that Rhapsody in Blue is one of my very favorite pieces of music. Here is the full rhapsody, played by an all-star group of top musicians conducted by one of the greats, Gerard Schwarz, featuring the amazing Lola Astanova on piano.

We have certainly come a long way from the original 1924 acoustic recording.

Further Reading

For more great articles on broadcast audio history, check out these items:

John Vassos: Celebrating a Visionary Broadcast Industrial Designer

The Empire State Building: Where it All Began

A Step into the Vintage Gear Time Machine

Telos Alliance has led the audio industry’s innovation in Broadcast Audio, Digital Mixing & Mastering, Audio Processors & Compression, Broadcast Mixing Consoles, Audio Interfaces, AoIP & VoIP for over three decades. The Telos Alliance family of products include Telos® Systems, Omnia® Audio, Axia® Audio, Linear Acoustic®, 25-Seven® Systems, Minnetonka™ Audio and Jünger Audio. Covering all ranges of Audio Applications for Radio & Television from Telos Infinity IP Intercom Systems, Jünger Audio AIXpressor Audio Processor, Omnia 11 Radio Processors, Axia Networked Quasar Broadcast Mixing Consoles and Linear Acoustic AMS Audio Quality Loudness Monitoring and 25-Seven TVC-15 Watermark Analyzer & Monitor. Telos Alliance offers audio solutions for any and every Radio, Television, Live Events, Podcast & Live Streaming Studio With Telos Alliance “Broadcast Without Limits.”

More Topics: Vintage Electronics, Vintage Audio Technology, Broadcast History

Recent Posts

Subscribe

If you love broadcast audio, you'll love Telos Alliance's newsletter. Get it delivered to your inbox by subscribing below!